Egypt under growing pressure as displaced Gazans crowd the border

Since Israel launched its retaliatory war in Gaza after the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, nearly 20,000 Palestinians have been killed and more than 50,000 wounded, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry. Whole swaths of the enclave are in ruins. The United Nations estimates 85 percent of its 2.2 million people have been displaced, heeding Israeli directives to flee to safer ground but often finding themselves on another battlefield.

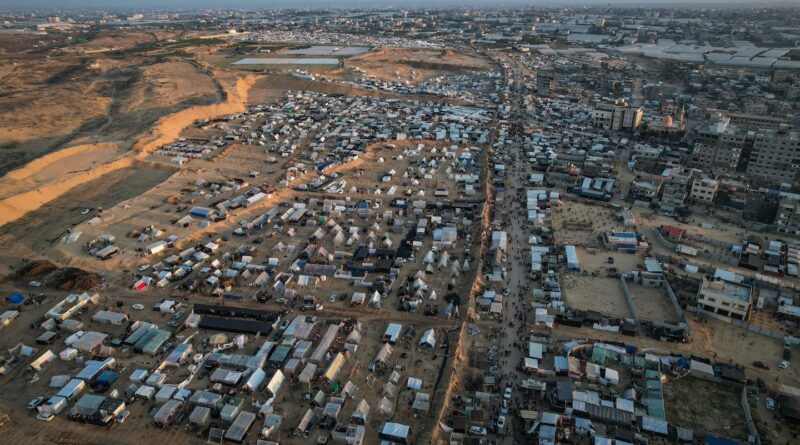

Many are sheltering in the southernmost city of Rafah, along the border with Egypt, where they are packed into homes, schools and tent encampments. Others sleep on the streets. Disease is spreading. Aid is far from sufficient to meet the overwhelming needs of civilians, and Israeli bombing has hampered its delivery.

“The Israelis have given assurances that whatever military steps are taken will not spill over into the Egyptian side of the border, but the humanitarian situation is dire,” a former Egyptian diplomat said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive security matter.

“You still have the prospect of an influx of Palestinians from Gaza into Sinai,” the former diplomat added. “Whether that happens as a result of a deliberate Israeli military strategy or by default … that may be a distinction without a difference.”

As the country reinforces its border in northern Sinai, top Egyptian envoys are doubling down on efforts to avoid such a scenario and push for a cease-fire.

Egypt has offered safe haven to millions of people who fled recent conflicts in Sudan, Libya, Yemen and Syria. But the mass dislocation of Palestinians during Israel’s founding in 1948 — known here as the Nakba, or “catastrophe” in Arabic — still looms large in the regional psyche. Arab governments fear that Israel will not allow Palestinians who leave Gaza to return after the war.

Remarks from some Israeli political figures calling for the removal of Palestinians from the enclave heightened that concern — as did a document from Israel’s intelligence ministry, leaked in October, which seemed to propose a permanent transfer to Egypt. Radical settler groups, key backers of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing government, are holding conferences to push for an Israeli resettlement of Gaza.

Netanyahu and senior defense officials maintain that Israel’s military objective is to defeat Hamas, not to depopulate the strip of Palestinians.

But “it’s an idea embraced by some of the right-wing leadership as a real option,” said Ksenia Svetlova, a senior nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council and former member of Israel’s parliament, the Knesset. “They don’t understand the complexity, overlook the risks, and fail to grasp how delicate the dynamics between Israel and Egypt are, dynamics that are worth preserving.”

With public sentiment in Egypt squarely behind the Palestinian cause, top officials here have made clear since Oct. 7 that Cairo will not abet another mass displacement. Egypt has facilitated the exit of thousands of foreign nationals and Palestinians affiliated with foreign entities via the Rafah border crossing since late October. But those who make it through are not allowed to stay in Egypt for more than a few days.

Cairo is also concerned about security, worried that Hamas militants will slip into northern Sinai.

“We reject the displacement of Palestinians from their land,” Egyptian President Abdel Fatah El-Sisi said in mid-October, warning that moving Gazans to Sinai would mean “transferring the attacks against Israel to Egyptian territory, which threatens the peace between Israel and a country of 105 million people.”

The Biden administration was concerned by Israeli discussions in the early days of the war about attempting to push Gazans into Egypt, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken and other top leaders pushed back hard, three senior U.S. officials told The Washington Post, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive conversations.

“The United States believes” that any eventual peace agreement “should include no forcible displacement of Palestinians from Gaza — not now, not after the war,” Blinken said last month.

Senior U.S., European and Arab officials who have worked closely with their Egyptian counterparts say Cairo’s position on the issue has been unwavering.

“There has never been any ambiguity or equivocacy on the part of the Egyptians about the displacement of the Palestinians from Gaza onto Egyptian territory,” a senior U.S. diplomat said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss delicate negotiations.

“Any ambiguity about this is radioactive in Egypt,” the diplomat added.

But conditions on the ground in Gaza have deteriorated substantially after more than two months of war.

Thaer Abu Aoun, 35, from Gaza City, has been displaced twice. He and his wife and their 2-year-old son are now in a tent in Rafah. Food is scarce, and the family has been forced to drink contaminated water, he told The Post in a phone call Monday. His son, Fares, has a constant fever and is terrified by the frequent explosions.

Abu Aoun said he fears Israel’s ground operation will soon unleash fighting and chaos in Rafah. “Then there will be nowhere to run,” he said.

“I am against leaving Gaza at all,” he said, calling it “illegal and inhumane.” But “if the borders with Egypt are bombed and the borders are opened to me, and I no longer feel that this place is safe for me and my family, I will not hesitate to save my family and go to Egypt.”

Egypt appears to be feeling the pressure, dispatching foreign minister Sameh Shoukry to Washington earlier this month to reiterate Cairo’s position. Egypt also led a nonbinding resolution last week in the U.N. General Assembly, which was approved overwhelmingly, calling for an immediate cease-fire.

U.N. Secretary General António Guterres told global policymakers in Doha last week that he expects “public order to completely break down soon” in Gaza, contributing to “increased pressure for mass displacement into Egypt.”

A border breach would not be unprecedented: In 2008, thousands of Palestinians rushed into Egypt temporarily after Hamas militants blasted a hole in the border wall.

“This was really a traumatic moment for the Egyptians, and they do not want this event to repeat itself. So I’m quite sure that the two sides are very much coordinated” as the IDF pushes south, said Michael Milshtein, a former adviser to Israel’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, which oversees Israel’s civilian policy in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

But if Palestinians do rush the border, “at the end of the day, you can’t leave people to die,” a former Arab diplomat said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive deliberations. “The political position is one thing, but the necessities on the ground and what is forced on the ground is a different story.”

In that event, the former diplomat added, Egypt would likely seek assurances from the United States and Israel that any displacement of Palestinians would be temporary.

In the meantime, Egypt has constructed a concrete wall and earthen berms along its side of the border, according to video footage published Saturday by the Sinai Foundation for Human Rights, a U.K.-based monitoring group with a team in northern Sinai. The military has also beefed up its presence. During two media tours in October, a Post reporter saw rows of tanks and military vehicles positioned along the road to Rafah.

As tensions grow along the border, the relationship between Cairo and Israel — strengthened through closer security cooperation in recent years — is at risk of breaking down, according to Mirette Mabrouk, director of the Egypt Studies program at the D.C.-based Middle East Institute.

“It is not in Israel’s interest to destabilize Egypt in any way,” she said.

Birnbaum reported from Washington. Itay Stern in Tel Aviv and Hajar Harb and Meg Kelly in London contributed to this report.