Analysis | The powerful lesson behind Pakistan’s stunning election result

Candidates linked to jailed ex-prime minister Imran Khan’s Movement for Justice party, known by its Urdu acronym PTI, won at least 93 seats in Pakistan’s National Assembly. That put them ahead of the center-right party led by another former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, who was widely seen as the candidate favored by Pakistan’s generals to lead the next government in a country where an election is often pejoratively cast as a “selection.”

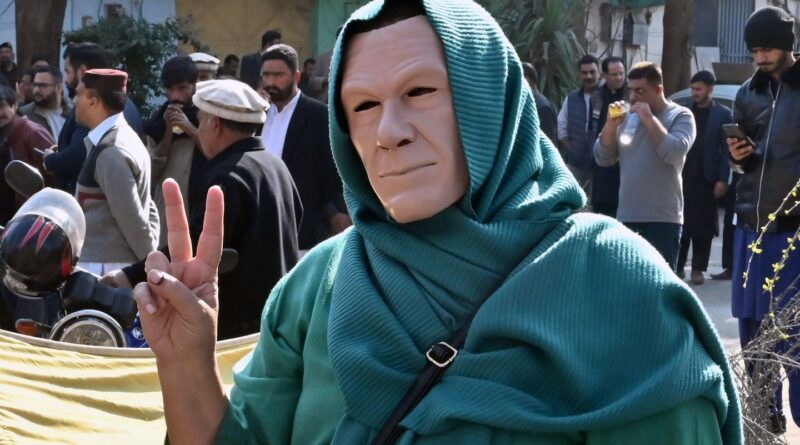

Khan, who was ousted from power in 2022 amid a fallout with the top brass, is languishing behind bars on the back of four separate court convictions that his supporters consider politically motivated. A barrage of lawfare kept him personally out of contention and forced PTI allies capable of contesting the vote to run only as independents.

Nonetheless, Pakistani voters saw the repressive tactics deployed against PTI and appeared to rally around the beleaguered faction. Khan’s party also used a considerable footprint on social media and technology like AI to get their leader’s message to voters, no matter the legal constraints set against them. On Sunday, PTI officials still pointed to apparent evidence of vote-rigging in more than a dozen seats they claimed they should have won and launched a flurry of court actions to contest those results.

But even the current mandate they secured is startling. “The vote was an astonishing display of defiance. This was supposed to be the most predetermined election in Pakistani history,” Omar Waraich, special adviser at the Open Society Foundations and a longtime Pakistan watcher, told me. “Instead, it became a peaceful revolt against the powerful military establishment.”

Khan and his populist PTI came to power in 2018 via an election that was, at the time, viewed as one where the military exerted its control on the levers of power in his favor. At the time, Sharif was the politician drowning under court cases and later fled the country in self-exile. But cracks emerged in Khan’s relationship with the military, and broader frustrations with his demagogic handling of government eventually snowballed into a political crisis that saw his rule ended in a vote of no-confidence. To this day, Khan and his allies fume over the deep state intrigues — and alleged U.S. interference — that drove him from power.

The interim regime that followed included both Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) and the center-left Pakistan People’s Party, led by the son of slain former prime minister Benazir Bhutto. Both parties are run as fiefdoms of dynastic families and have long been fixtures in Pakistani politics. But they struggled, as Khan did, with the economic dysfunctions afflicting the country and failed to secure much popular support. Sharif and others in Pakistan’s civilian political establishment pinned their hopes on a fresh election to boost their legitimacy.

That did not come to pass, even as the military-led deep state seemed to go out of its way to hobble PTI’s chances. “The Pakistani electorate defied all odds and an array of massive electoral barriers to deliver a clear message: that they no longer welcome the military’s interference in politics, and that they have moved on from the two dynastic parties that have governed Pakistan for decades,” Madiha Afzal, a Pakistan scholar at the Brookings Institution, told me. “That message in itself is a moment of hope for Pakistan’s democracy.”

It’s far from certain that PTI-linked politicians will form the next government. Sharif’s party technically won the most seats, since Khan’s allies were not allowed to run under their party banner. Some of these elected lawmakers could still defect to a broader coalition led by Sharif, who on polling day boasted that he wouldn’t even need coalition talks to win his fourth term in office.

“A future government could include some candidates who ran on the ticket of Khan’s party. All of its candidates had been ordered by a court to run as independents in the lead-up to the election, which now opens up the possibility of rival parties poaching some of them in the coming days,” my colleagues Rick Noack, Shaiq Hussain and Haq Nawaz Khan reported from Islamabad. “This could turn upcoming coalition talks into a particularly fraught process and deepen polarization between Khan’s supporters and his opponents in this nuclear-armed country of 240 million.”

The country’s military authorities may be chastened by the vote. But they could also see the outcome as further grounds to tighten their hold on the reins of power. “The past may be another country as the election demonstrated,” wrote Pakistani commentator Abbas Nasir, gesturing to Pakistan’s fitful attempts to overcome a legacy of military coups and interventions. “But we aren’t known to learn from our mistakes. It is true that you can ‘manage’ the electoral process — but only to a point and no more.”

Any outcome that freezes PTI out of power will inevitably be seen as suspect. “The legitimacy of these elections has come into serious doubt so they will have no credibility in the eyes of the people,” Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, a former Pakistani prime minister, told the Guardian. “The only way they can obtain legitimacy is to include Imran Khan. Any solution without Khan will not be workable. But the question is: will the [military] establishment accept that?”

The generals may hear the warnings in statements from governments and officials elsewhere, including some U.S. lawmakers, urging Pakistani authorities to uphold democracy and avoid election interference. But it’s the voices closer to home that grew even louder.

“With the odds stacked impossibly high against them, voters reclaimed their democracy,” Waraich said. “While Khan’s party has been denied a majority, and may not form a government, it’s clear that there’s now an irreversible trend. Young Pakistanis are clear that it is they, and not the men in uniforms, that will make decisions about their future.”