Daniel Kahneman was a master of teasing questions

Winners of the Nobel prize in economics tend to sprinkle their papers with equations. Daniel Kahneman, who died on March 27th, populated his best-known work with characters and conundrums. Early readers encountered a schoolchild with an IQ of 150 in a city where the average was 100. Later they pondered the unfortunate Mr Tees, who arrived at the airport 30 minutes after his flight’s scheduled departure, and must have felt even worse when he discovered the plane had left 25 minutes late. In the 1970s readers had to evaluate ways to fight a disease that threatened to kill 600 people. In 1983 they were asked to guess the job of Linda, an outspoken, single 31-year-old philosophy graduate.

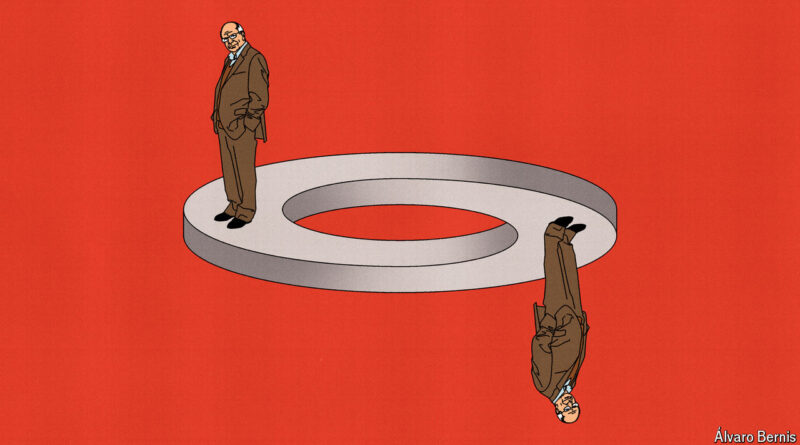

Kahneman used such vignettes to expose the seductive mental shortcuts that can warp people’s thoughts and decisions. Many people, for example, think it more likely that Linda is a feminist bank-teller than a bank-teller of any kind. Presented with two responses to the disease, most choose one that saves 200 people for certain, over a chancier alternative that has a one-third chance of saving everyone and a two-thirds chance of saving no one. But if the choice is reframed, the decision is often different. Choose the first option, after all, and 400 people die for sure. Choose the second and nobody dies with a one-third probability.