Sanctions crushed Syria’s elite. So they built a zombie economy fueled by drugs.

KOM AL-RAF, JORDAN

On clear days, the Syrian villages along the border here look deceptively empty. The Jordanian soldiers peering north across no man’s land see only dusty ghost towns where nothing moves except feral dogs and an occasional farmer working fields that have seen too little rain and too much war.

But on nights when the fog rolls in over the hills, the frontier takes on a sinister, alternate existence. Dozens of men — in trucks, on dirt bikes and on foot — emerge from the mist to form heavily armed columns for a race across the border.

They carry assault rifles, rocket-propelled grenades, even machine guns. Concealed in their vehicles and backpacks are hundreds of packages containing many tens of thousands of small white pills. The drugs, a synthetic stimulant called Captagon, are fresh from factories in the Syrian heartland that churn out an estimated $10 billion worth of illicit drugs each year.

In a country where traditional industry has all but ceased to exist, the pills are the fabulously profitable core of a zombie economy that has helped Syria’s political and military elite cling to power after 13 years of civil war and a decade of crushing sanctions. Having swollen to a massive scale with tacit government approval, according to U.S. and Middle Eastern officials, the trade increasingly threatens Syria’s neighbors, flooding the region with cheap drugs.

“If visibility is bad, they are coming — every single time,” said Col. Essam Dweikat, commander of a Jordanian Armed Forces unit responsible for defending the western sector of the country’s 200-mile border with Syria. “The problem is, the people who come across now are armed, and they are ready to fight.”

Jordan has twice dispatched fighter jets into Syrian airspace to carry out strikes against smugglers and their safe houses, according to intelligence officials in the region — operations the government in Amman has not acknowledged publicly.

Yet, despite extraordinary efforts to stem the tide, billions of Captagon pills from dozens of manufacturing centers continue to pour across Syria’s borders and through its seaports. The trade’s ripple effects are expanding ever outward, to include rising levels of addiction in wealthy Persian Gulf countries and the appearance of drugmaking labs in neighboring Iraq and as far away as Germany, according to Iraqi and German officials.

Huge profits from the pills — which cost less than a dollar to make but fetch up to $20 each on the street — have attracted a host of dangerous accomplices, from organized crime networks to Iranian-backed militias in Lebanon, Iraq and Syria, according to U.S. and Middle Eastern intelligence officials. In recent months, smugglers began moving weapons as well as drugs, the officials said. Jordanian raids on smuggling convoys have netted rockets, mines and explosives apparently intended for Islamist extremists in Jordan or possibly for Palestinian fighters in Gaza and the West Bank.

Most profoundly, the drugs have provided a lifeline for the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who has seized on Captagon as a way to stay in power, current and former U.S. officials said. As the United States and other Western countries ramped up pressure with sanctions — to hold Syrian officials accountable for war crimes or to pressure Assad to negotiate an end to the conflict — Syria’s ruling class found salvation in a small white pill, one that conferred massive profits and partial insulation from the punishment U.S. policymakers were serving up.

“This is the stream of revenue on which they are relying in the face of sanctions pressure from us and from the European Union,” said Joel Rayburn, the U.S. special envoy to Syria from 2018 to 2021. “The Assad regime could not withstand robust sanctions enforcement, except for Captagon. There is no other source of revenue that could make up for what they lost due to sanctions enforcement.”

The Syrian mission to the United Nations did not respond to a request for comment. The Assad government has repeatedly denied having any involvement with illicit drugs, and in the past year, it announced arrests of several low-level traffickers and the seizure of small quantities of the white pills. Yet Treasury Department documents have identified close relatives of Assad — including his brother Maher al-Assad, commander of the Syrian army’s 4th Armored Division — as key participants in Captagon trafficking. Most of the pills are produced in regime-held areas and moved through borders and port facilities under government control.

A 2023 study extrapolating from known seizures of drugs since 2020 estimated that Captagon generates about $2.4 billion a year for the Assad regime, “well above any other single licit or illicit source of revenue,” wrote the authors at the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks, a nonprofit that conducts research on organized crime and corruption in Syria.

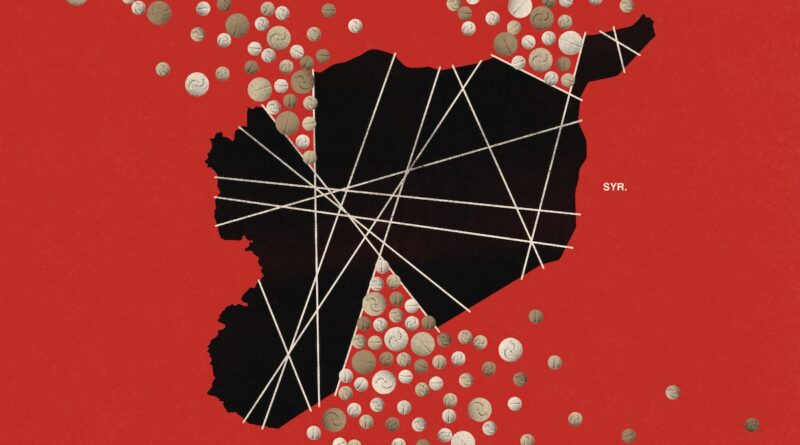

How Captagon makes its way through Syria

The industry’s rise illustrates the complexities of trying to change a foreign power’s violent repression by ratcheting up economic pressure on its leadership and business elites. U.S. officials and experts say sanctions remain the most powerful tool, short of war, for punishing a government that has been accused of numerous war crimes since Assad began brutally crushing a pro-democracy uprising in 2011.

The long list of offenses includes the systematic torture and executions of civilians, the deliberate targeting of hospitals and food distribution centers, and the killings of hundreds of women and children with outlawed sarin nerve gas, according to U.S. officials, U.N. investigations, and human rights and exile groups. Syria is officially listed by the United States as a sponsor of international terrorism and is regarded as an increasingly vital ally and strategic partner to Russia and Iran.

Assad has defied calls for his ouster while presiding over the destruction of this once moderately prosperous country of 22 million. At least 12 million Syrians are now refugees or internally displaced, and 90 percent of the country’s citizens live in poverty. The country’s GDP fell from a prewar high of $252 billion to just $9 billion in 2021, according to World Bank estimates. The economy continues to shrink, as does the life expectancy for young Syrians.

The emergence of industrial-scale Captagon production beginning around 2019 prompted U.S. officials and Congress to shift the focus of sanctions to specifically target the drug trade and its sponsors. In April, Congress approved legislation targeting Syria’s drug kingpins as part of the $95 billion bipartisan foreign aid package signed into law by President Biden. That followed a Treasury Department announcement of new sanctions against Syrian business executives with alleged ties to Captagon smuggling.

Yet Captagon production continues to soar, and Assad is unshaken and apparently wealthier than ever, U.S. officials acknowledge. While the sanctions imposed against his government enjoy broad support among Syrian opposition leaders and human rights advocacy groups, the experience of the past decade underscores a perplexing reality: While sanctions remain a vital tool for punishing criminal behavior by governments, the targets of sanctions inevitably find ways to blunt their impact, often with painful consequences for ordinary citizens.

“The most profound point is that sanctions strengthen the bad actor relative to the rest of the population,” said Ben Rhodes, the former deputy national security adviser for the Obama administration who worked on Syria policy in the early years of the civil war. “The people who are most able to withstand this are the people with guns and power.”

A state enterprise

Syria’s Captagon crisis came on fast and hard.

A few well-connected Syrians and Lebanese nationals built the foundations for a vast drug empire amid the chaos of the country’s fragmentation.

Before the start of the conflict in 2011, Captagon was regarded as a niche product for a small number of crime groups in Lebanon and Turkey. These manufacturers developed a knockoff version of the drug that was first developed in the 1960s by a German pharmaceutical company and marketed under the Captagon brand. The original version combined amphetamine with a second drug that stimulates the central nervous system. It was used by German physicians to treat hyperactivity and depression until the 1980s, when U.S. regulators and the World Health Organization recommended outlawing it because of the high risk for abuse.

Beginning around 2018, U.S. and Middle Eastern officials said, cottage-scale manufacturing of the drug in Lebanon expanded to a handful of Syrian towns in a border region north of Damascus.

A key figure, according to Treasury Department sanctions documents, was Hassan Daqqou, a dual Syrian-Lebanese national and onetime car dealer who began buying up properties on both sides of the border for production centers and warehouses. Daqqou — dubbed the “King of Captagon” by the Lebanese news media — succeeded in building his empire through alliances with powerful friends within government and security circles in Syria and Lebanon.

Among his collaborators, U.S. and Middle Eastern officials said, were operatives with the Lebanese militia group Hezbollah as well top Syrian political and military leaders — not only Maher al-Assad, but also several Assad cousins and business executives close to the Syrian leader.

“

“The most profound point is that sanctions strengthen the bad actor relative to the rest of the population. The people who are most able to withstand this are the people with guns and power.”

Ben Rhodes,

former deputy national security adviser for the Obama administration

Two Biden administration officials, citing U.S. intelligence assessments, confirmed in interviews that Maher’s 4th Division has been an active participant in the Captagon trade since at least 2020, controlling distribution and transportation hubs, including port facilities in Latakia on the Syrian coast. Syrian control of operations increased after Daqqou was imprisoned in Lebanon for drug trafficking in 2021.

Biden administration officials say they have no evidence that Assad is personally directing the Captagon trade. But by naming his brother and cousins as key facilitators, U.S. officials made clear their view that drug manufacturing in Syria is now a state enterprise.

“Syria’s security forces now provide protection for drug traffickers,” said one Biden administration official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss intelligence assessments. White House officials believe Assad is now using Captagon as leverage with Arab states, offering to selectively restrict the flow of drugs as a reward to governments that normalize ties with Syria.

“It is clear that he could shut this down if he wanted to,” the administration official said.

Also clear is the massive scale of drug manufacturing in Syria, which U.S. officials say now produces most of the world’s Captagon supply. Administration officials say ingredients for the drug, such as amphetamine, are purchased legally from several countries, including Iran and India, and imported through Latakia. The precursor chemicals are mixed in factories and machine-pressed into tablets bearing a distinctive double-C logo.

Since the start of the decade, law enforcement agencies intercepted huge shipments of Syrian-made drugs in busts at ports in Italy, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia. In 2021, the Malaysian authorities discovered more than 95 million Captagon tablets hidden inside a cargo ship — a record haul with a street value of $1.2 billion that was routed through Malaysia to hide its ultimate destination: Saudi Arabia.

The biggest maritime busts showed smugglers going to extraordinary lengths to conceal their cargo. The 84 million tablets seized by customs officials in the Italian seaport of Salerno in 2020 had been hidden inside industrial-size spools of paper. Saudi police found millions of the white pills stashed inside containers of pomegranates and flour in separate incidents in August 2022 and April 2023. In one of the most recent attempts, uncovered by Dubai investigators this past September, drug traffickers hid 86 million pills inside prefabricated wooden panels and doors labeled for delivery to construction companies. Nearly all the pills were traced back to ports in Syria.

While it’s not technically accurate to call Syria a narco-state — Captagon is a stimulant, not a narcotic — the country has become so dependent on drug income that Assad would be hard-pressed to shut down the drug factories if he decided to, said Caroline Rose, a researcher who oversees the Special Project on the Captagon Trade at the New Lines Institute, a Washington nonprofit.

“They’ve taken Captagon to such a level that the industry can sustain itself,” Rose said. “It’s no longer mobile facilities, but permanent factories that can accommodate industrial-scale production. And on top of that, there’s an active security apparatus that provides guards, protection and support and even facilitates the movement of the drugs.

“It’s a perfect system,” she said.

Running battles

For Syria’s neighbors, it’s a disaster.

Captagon has now become a drug of choice — and a public health crisis — among young people across the Middle East, making deep inroads in countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates where alcohol is banned or, for locals, proscribed. Habitual use brings addiction and a wide array of health problems, from insomnia and depression to hallucinations and heart problems, according to medical researchers.

The drug is also a tool for Islamist groups, including Islamic State militants, because it provides users with a burst of euphoric energy and a feeling of invincibility and emotional detachment on the battlefield. Some fighters call it “Captain Courage.”

Surging drug trafficking has forced Jordan to deploy hundreds of soldiers on its northern border. In the past year, Jordanian forces have waged running battles with groups of up to 100 traffickers that left multiple people dead and wounded on both sides.

On a recent late-winter afternoon near Kom al-Raf, a dozen soldiers in full combat gear traced the southern edge of no man’s land, checking for signs of breaches in the barrier system of berms and coiled concertina wire. As they walked, other soldiers stood guard from atop armored vehicles and watchtowers that have been erected at half-mile intervals along the perimeter road. In recent months, officers said, the smugglers had begun using drones to conduct surveillance or, in some cases, to ferry small parcels to confederates across the border.

But vastly more drugs are hauled overland. Near Kom al-Raf, a firefight in 2022 killed a Jordanian soldier when his patrol surprised a large column of smugglers — at least 68 gunmen on foot, according to the after-action report — as they attempted to cross in dense fog.

A map of the Syria-Jordan border where smugglers transport Captagon.

After a brief firefight, the smugglers fled back into Syria, leaving behind 100-pound packs filled with Captagon tablets as well as bolt-cutters and weapons, Jordanian officials said.

The convoy’s large size and willingness to engage a military patrol startled the Jordanians and prompted army commanders to adopt more aggressive measures.

“We’ve had to change our rules of engagement multiple times because their methods have changed,” Brig. Gen. Mustafa al-Hiyari said in an interview at the headquarters of the Jordanian Armed Forces, perched on a heavily fortified hilltop just outside Amman. “Smugglers generally don’t want to fight, but these are armed.”

Since 2020, the border region has seen at least a dozen armed clashes that resulted in deaths, injuries or arrests. One encounter in January resulted in the capture of 15 alleged traffickers, according to photos shown to The Washington Post. Jordanian officials said the men acknowledged during interrogations that they had undergone professional military training to qualify for the job of courier. At the time of the arrests, several were high on Captagon, the officials said.

In one of the most recent cases, Jordanian authorities tracked a suspected drug shipment last month as it traversed more than 100 miles of open highway before police swooped in at a border crossing with Saudi Arabia. Millions of pills were found hidden inside construction equipment bound for the gulf kingdom, officials said.

Based on interrogations and other evidence, Jordanian intelligence officials said they have concluded that the most recent bands of smugglers are linked to Iranian-backed Syrian militias, including some of the same groups that have fired rockets at U.S. forces based in eastern Syria. There is no evidence of direct involvement in drug trafficking by Tehran, but Iranian officials have provided weapons, money and intelligence to the groups.

U.S. and Jordanian officials say the militias may be responsible for the increasingly sophisticated weapons carried by traffickers. In several instances, smugglers have left caches of weapons inside Jordanian territory, possibly with the intention of providing them to other Iranian-backed militants in the West Bank or the Gaza Strip. The Post was shown photos of some of the hidden weapons, which included Claymore-type anti-personnel mines.

“The Iranian proxy groups operate like warlords,” constantly competing for fighters, better weapons and cash, said Charles Lister, director of counterterrorism programs at the Washington-based nonprofit Middle East Institute. “Drugs are just an easy way to make money and become more powerful than your neighbors.”

‘In an underworld’

The U.S. policy of maintaining harsh sanctions enjoys broad bipartisan support. The toughest measures to date came in 2020, nine years after the start of the war and the same year that the first massive seizures of Captagon drugs were being recorded. The congressionally approved Caesar Act was named in honor of a Syrian military photographer and defector — known publicly only as “Caesar” — who used his camera to document the Assad regime’s torture and murder of more than 11,000 Syrian prisoners. The sanctions targeted the country’s largest remaining industrial sectors, including energy production and construction, and are explicitly intended to discourage international business agreements that could help Assad repair the country’s battered infrastructure.

As a means of inflicting well-deserved punishment on Syria’s leader, the sanctions are widely regarded as a triumph. Supporters of the measures warn that the world cannot “normalize” Assad or allow his regime to enrich itself through construction contracts to rebuild cities that Assad helped to depopulate and destroy.

The Caesar Act, together with this year’s Captagon sanctions, sends an important signal to the Assad regime and its allies that the United States is standing with ordinary Syrians, said Mouaz Moustafa, executive director of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, a Washington-based nonprofit that advocates for victims of Syrian war crimes.

“There are strict humanitarian exceptions to ensure that no Syrian civilians, regardless of their political outlook, are harmed by these sanctions,” Moustafa said. “The sanctions are focused on the people who are harming ordinary Syrians with chemical weapons, torture and indiscriminate bombardment. The drugs were part of a deliberate strategy by these same people to ensure that they have a revenue source, and that they have complete control over it.”

Yet even the most ardent supporters acknowledge that no “victory” in Syria is completely clean.

While there may be few viable alternatives to sanctions, the measures always come with unwanted side effects — including the inevitable certainty that the elites of society will find ways to survive and even profit, said Peter Andreas, professor of international studies at Brown University and the author of a study on how sanctions increase illicit trade.

“The targets of sanctions, because their survival depends on it, are willing to go through all kinds of alliances to succeed,” Andreas said.

Sanctions can eventually “put the whole economy in an underworld,” he said. “It’s an unintended but very real and long-lasting consequence.”