Water is running out in Gaza. It will mean more deaths.

Clean water was already hard to come by in Gaza before the war. Now, as fuel runs out and only small amounts of aid are allowed in, it is becoming nearly impossible to find.

Palestinians in Gaza spend their days figuring out where to get water and how to divide what they have among family members, even as they seek shelter from Israeli airstrikes.

UNRWA, the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, has warned that “people will start dying without clean water.”

On Oct. 9, Israel enforced a full blockade of the strip that cut off all sources of water, electricity, food and fuel. Since then, they have allowed a trickle of aid and water to flow into southern Gaza, but not the north. Fuel — which is essential for water pumps and desalinization — remains cut off. Israeli officials have said they are not allowing fuel into the besieged enclave so that it doesn’t get into the hands of Hamas fighters.

Abeer al-Bayad has four children. The youngest, Hassan, is just 8 weeks old. Since the war began, al-Bayad said her baby cries for hours. She thinks he is hungry because she isn’t producing enough breastmilk to feed him.

She is staying in a house with two dozen people, more than 10 of them children, with little access to clean water.

“I am drinking 250 milliliters (8 ounces), a small bottle of water [a day],” al-Bayad said. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends that nursing moms drink 64 to 96 ounces (1.9 to 2.8 liters) of water a day.

A lack of potable water also puts Gazans at risk of dehydration and waterborne diseases like cholera, typhoid and hepatitis.

Why does Gaza need water?

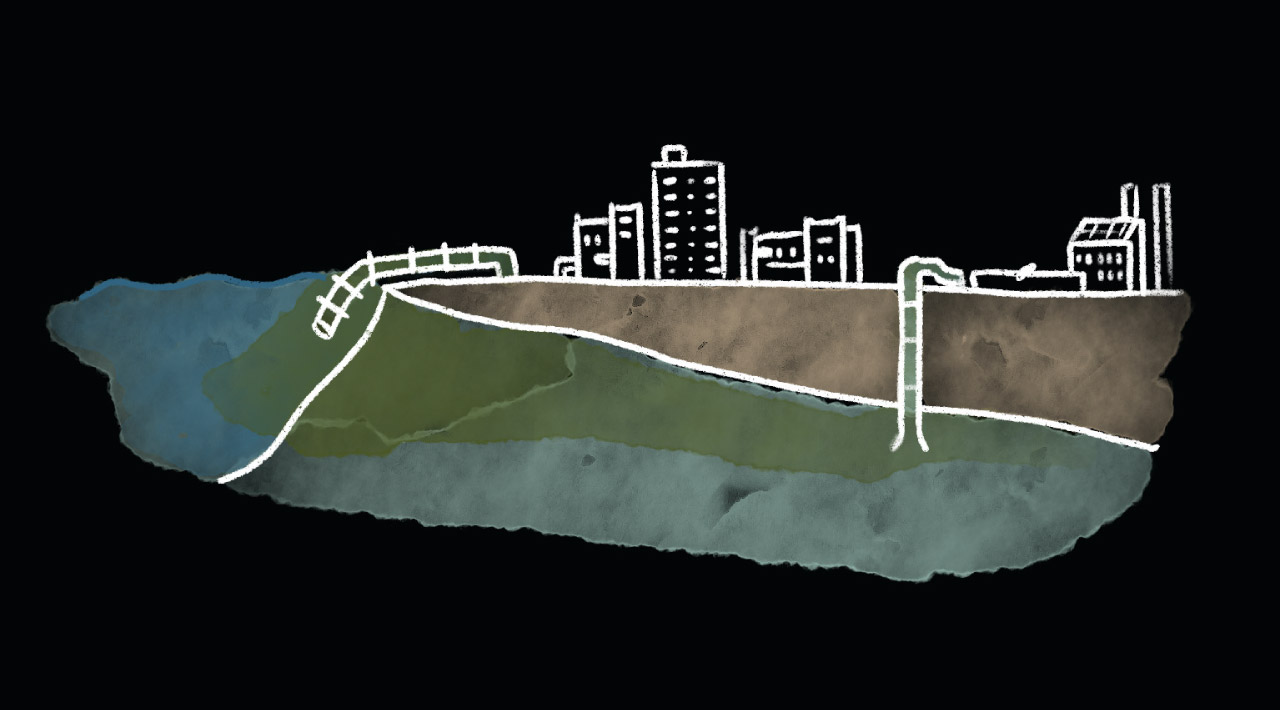

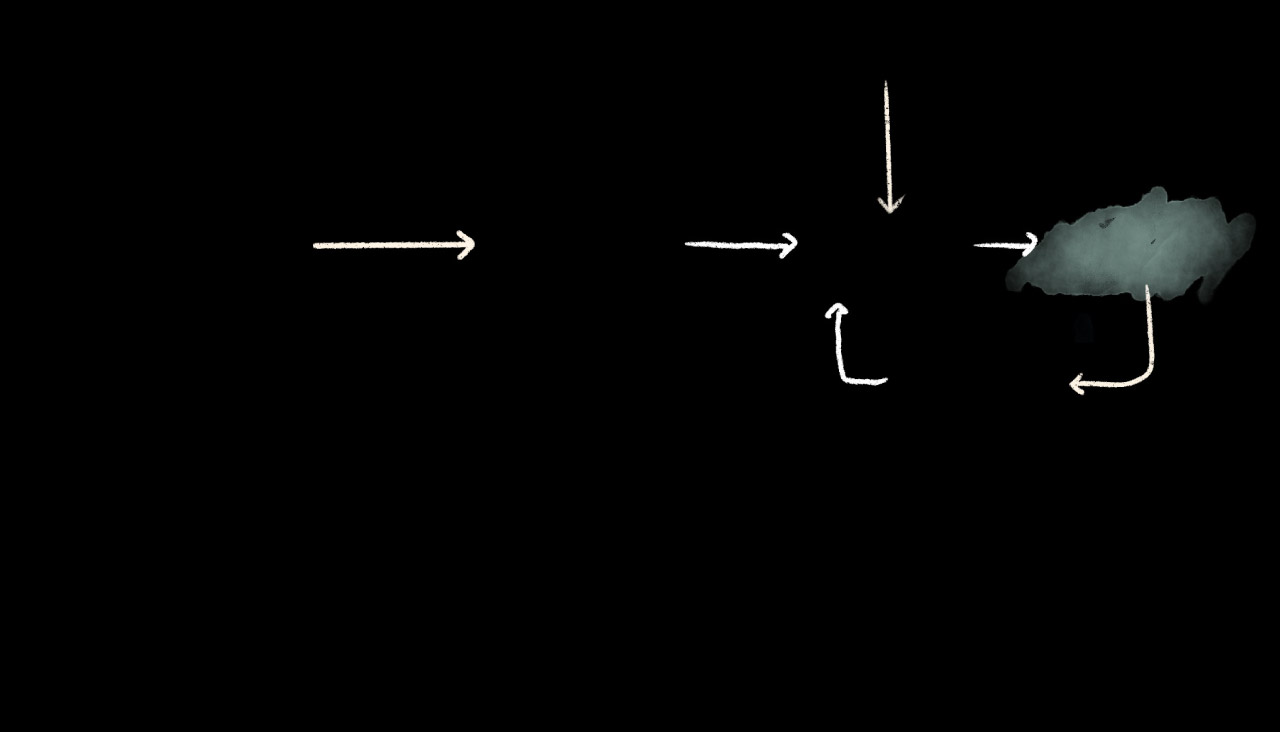

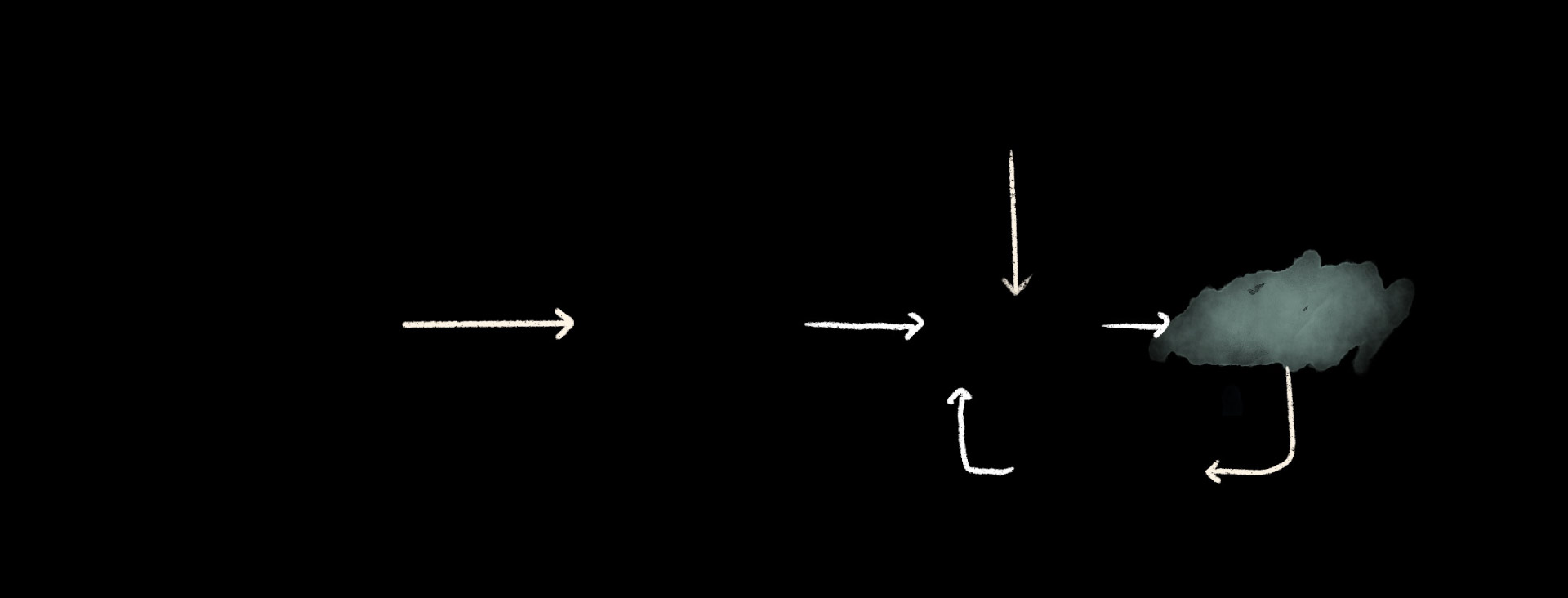

Cross section of the water supply in Gaza.

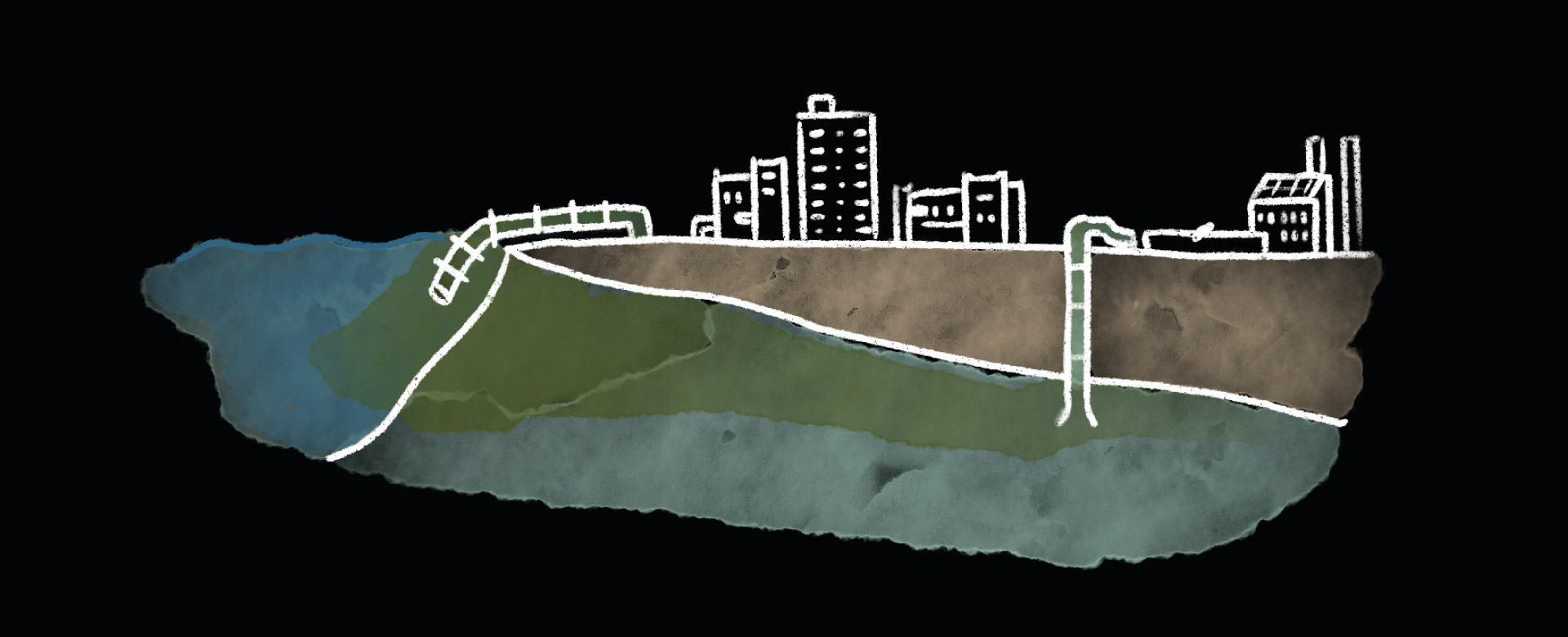

Cross section of Gaza’s water supply with waste water added.

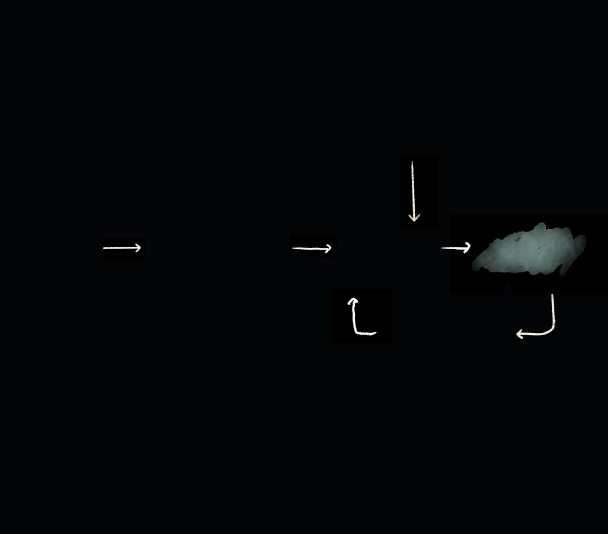

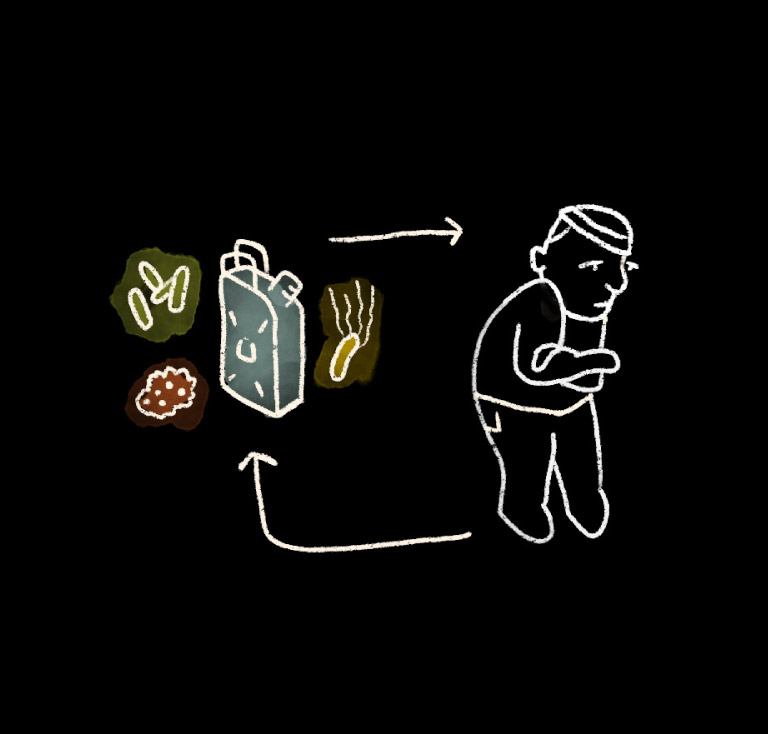

A diagram of how water could flow in Gaza under normal circumstances.

A majority of Gaza’s water supply is pumped from a coastal aquifer that sits below the sandy ground. Because it’s so close to the sea, the water from the aquifer is brackish.

1 / 8

Decades of untreated wastewater and infrastructure damaged in past conflicts make the water even more unhealthy. According to the United Nations, more than 95 percent of water from the coastal aquifer is not drinkable.

2 / 8

This diagram shows Gaza’s water supply under ideal circumstances. Surface water and dependable power would make pumping, desalinating and treating the water possible.

3 / 8

But there has been no natural surface water in Gaza since the early 2000s. The enclave is left to depend on Israel’s National Water Carrier to supplement its groundwater sources.

4 / 8

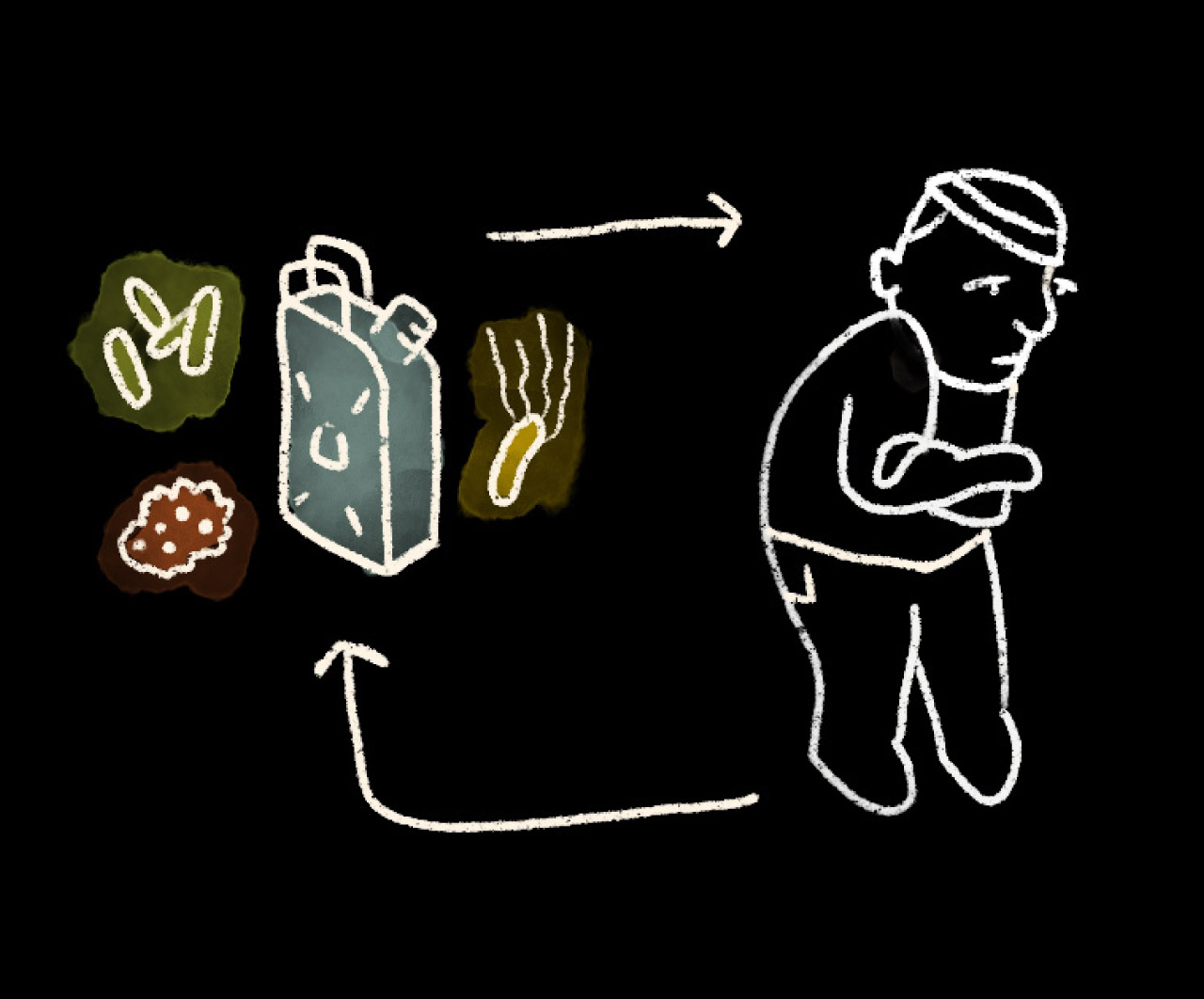

Without electricity and dwindling fuel, Gaza’s water treatment facilities are barely working.

5 / 8

Gaza’s desalination infrastructure, while inadequate, is supposed to provide the majority of potable water to the strip’s residents.

6 / 8

Meanwhile, airstrikes and the lack of electricity are leeching sewage across the land and into the sea. The currents know no borders as the pollution drifts north.

7 / 8

As people seek refuge from the war, finding clean water is increasingly difficult. Aid trucks are trickling in from the Rafah crossing but are not bringing in nearly enough water. With no regular access to internet and cell service, people are unable to communicate with desalination companies about where to find water.

8 / 8

“The immediate risks when water is so constrained is dehydration,” said Syed Imran Ali, a research fellow at the Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research at York University. “It forces people to drink non-potable, unsafe sources of water. And that creates a situation where highly infectious waterborne diseases like cholera, typhoid and dysentery, those can start tearing through a population.”

More than 8,000 Palestinians have been killed since Oct. 7, according to the Gaza Health Ministry. Diminishing water supplies often lead to an increase in infectious disease, said Juliane Schillinger, a researcher on conflict and water at the University of Twente in the Netherlands.

“There’s this whole hidden part of indirect casualties … people who die weeks or months afterwards from impacts like lack of clean water,” Schillinger said.

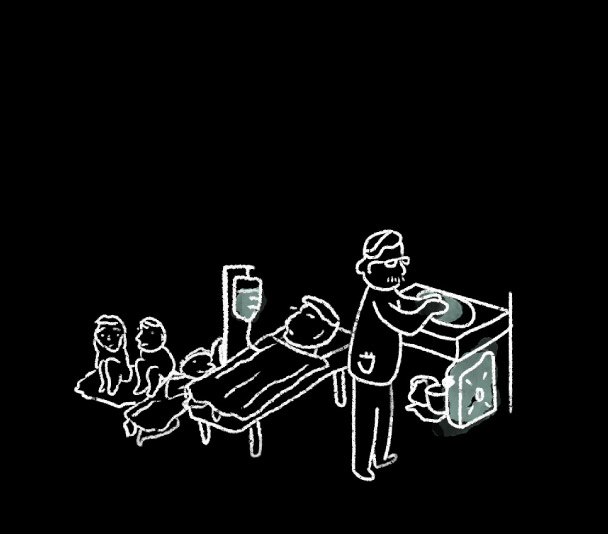

With hospitals over capacity and struggling to keep the lights on, they cannot handle another public health crisis.

Hospital

Gaza’s most vulnerable will be the worst affected “like children, like the elderly, pregnant women, people with disabilities,” Schillinger said.

In conflict areas, children under the age of 5 are 20 times more likely to die of diarrheal disease than to violence, according to UNICEF. Medications have run out.

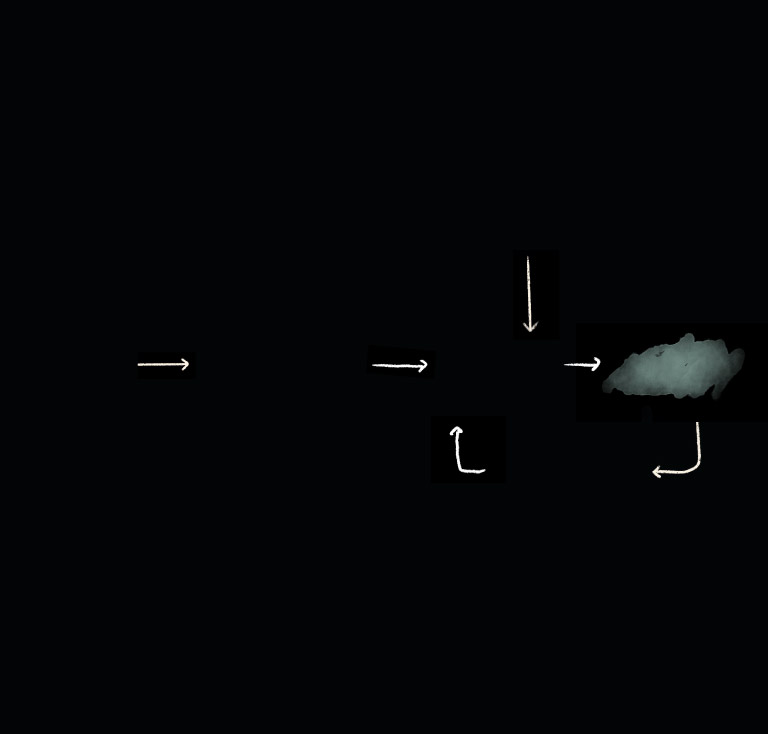

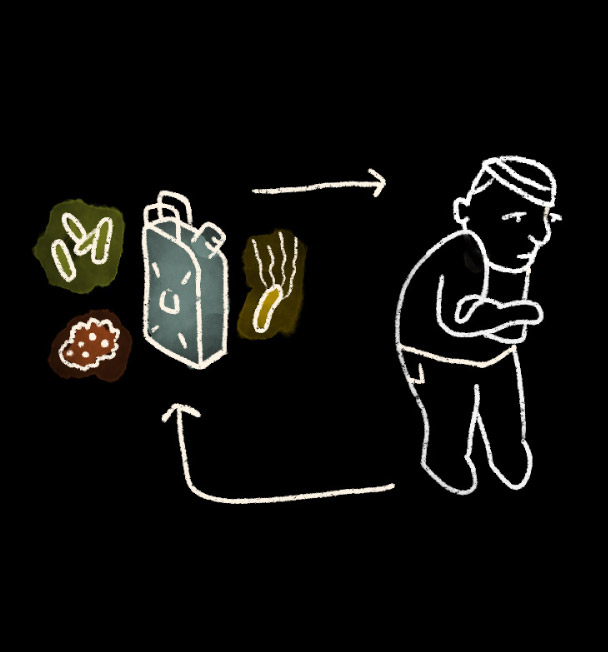

The vicious cycle of waterborne disease and unclean water.

“When the flow of water stops, diseases like cholera and diarrhoea can spread like wildfire, often with fatal consequences,” said Manuel Fontaine, the director of emergency programs, in the 2021 report.

Cholera is especially deadly. During the conflict in Yemen, more than 3,500 people died of the disease between 2016 and 2017, according to the Red Cross. After the 2014 Gaza War, cases of sanitation-related diseases tripled. .

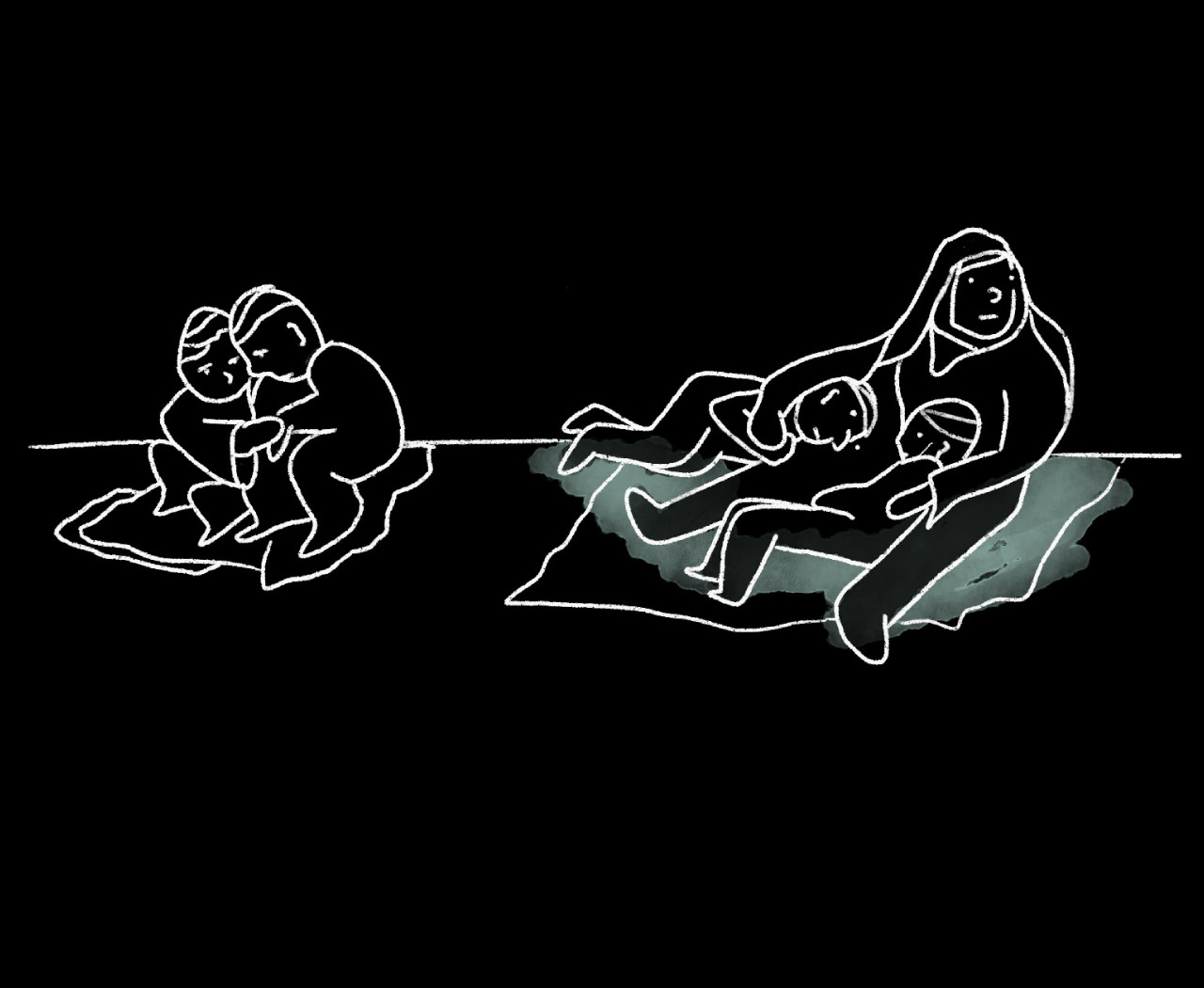

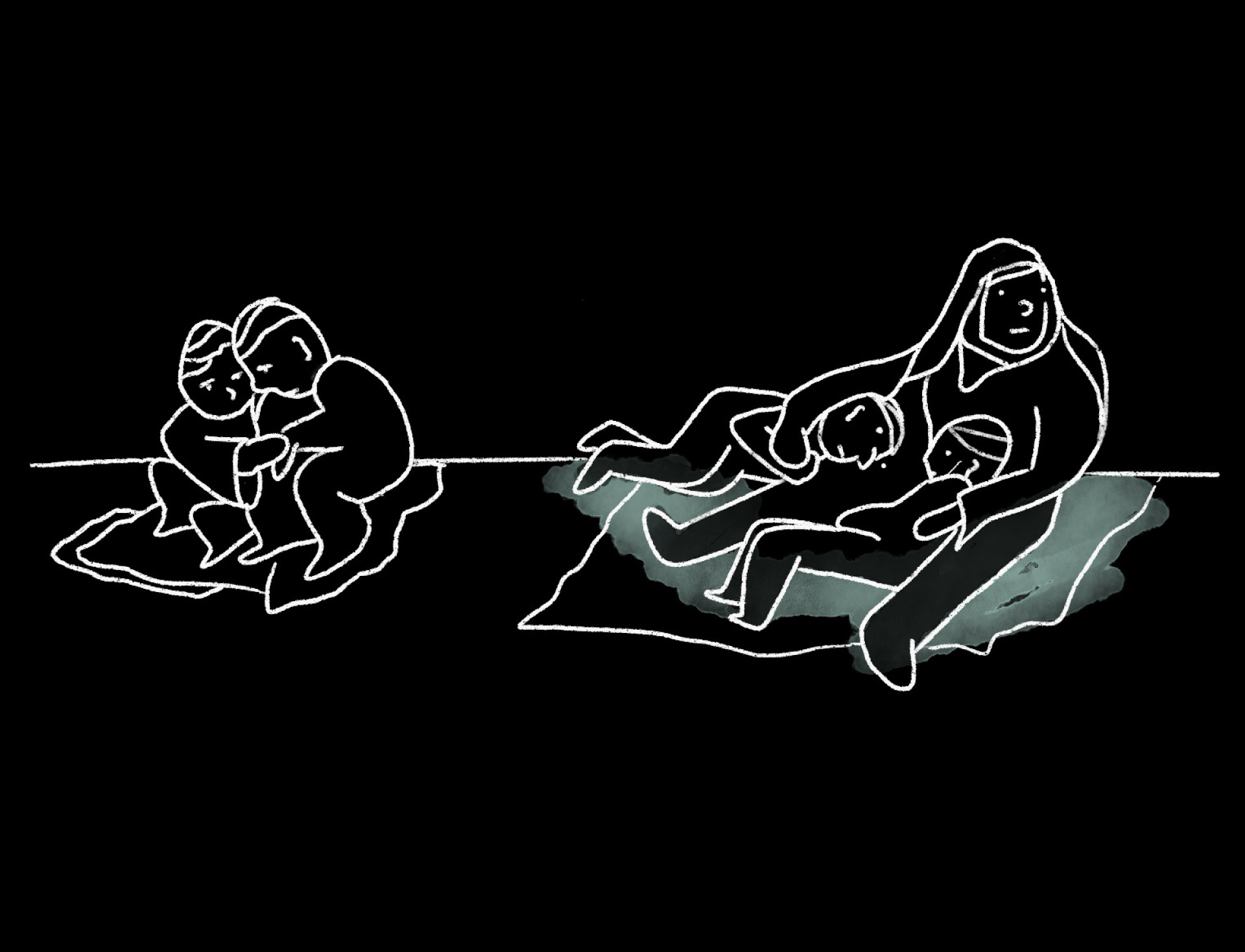

Al-Bayad said they are no longer able to bathe. Her oldest son shares his water with his younger sisters. Her husband drinks less so that he can give her more, as she tries to feed their baby.

This graphic closes out the story on clean water in Gaza. A woman is seen in a hallway holding two kids while two other hold one another.

Design and development by Daniel Wolfe. Additional work by Artur Galocha. Editing by Reem Akkad, Laris Karlis and Samuel Granados. Research by Cate Brown. Copy editing by Allison Cho.

Map sources: UN OCHA for desalination, power, water infrastructure locations and national water carrier data via: report from UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia report: Inventory of shared water resources in Western Asia.